Whence such strangely universal shortsightedness? The failure of Western experts to anticipate the Soviet Union's collapse may in part be attributed to a sort of historical revisionism -- call it anti-anti-communism -- that tended to exaggerate the Soviet regime's stability and legitimacy. Yet others who could hardly be considered soft on communism were just as puzzled by its demise. One of the architects of the U.S. strategy in the Cold War, George Kennan, wrote that, in reviewing the entire "history of international affairs in the modern era," he found it "hard to think of any event more strange and startling, and at first glance inexplicable, than the sudden and total disintegration and disappearance … of the great power known successively as the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union." Richard Pipes, perhaps the leading American historian of Russia as well as an advisor to U.S. President Ronald Reagan, called the revolution "unexpected." A collection of essays about the Soviet Union's demise in a special 1993 issue of the conservative National Interest magazine was titled "The Strange Death of Soviet Communism."

Were it easier to understand, this collective lapse in judgment could have been safely consigned to a mental file containing other oddities and caprices of the social sciences, and then forgotten. Yet even today, at a 20-year remove, the assumption that the Soviet Union would continue in its current state, or at most that it would eventually begin a long, drawn-out decline, seems just as rational a conclusion.

Indeed, the Soviet Union in 1985 possessed much of the same natural and human resources that it had 10 years before. Certainly, the standard of living was much lower than in most of Eastern Europe, let alone the West. Shortages, food rationing, long lines in stores, and acute poverty were endemic. But the Soviet Union had known far greater calamities and coped without sacrificing an iota of the state's grip on society and economy, much less surrendering it.

Nor did any key parameter of economic performance prior to 1985 point to a rapidly advancing disaster. From 1981 to 1985 the growth of the country's GDP, though slowing down compared with the 1960s and 1970s, averaged 1.9 percent a year. The same lackadaisical but hardly catastrophic pattern continued through 1989. Budget deficits, which since the French Revolution have been considered among the prominent portents of a coming revolutionary crisis, equaled less than 2 percent of GDP in 1985. Although growing rapidly, the gap remained under 9 percent through 1989 -- a size most economists would find quite manageable. Using 2010 figures, the total (American) debt (96.3% of GDP) ranked 12th highest against other nations.

The sharp drop in oil prices, from $66 a barrel in 1980 to $20 a barrel in 1986 (in 2000 prices) certainly was a heavy blow to Soviet finances. Still, adjusted for inflation, oil was more expensive in the world markets in 1985 than in 1972, and only one-third lower than throughout the 1970s. And at the same time, Soviet incomes increased more than 2 percent in 1985, and inflation-adjusted wages continued to rise in the next five years through 1990 at an average of over 7 percent.

Yes, the stagnation was obvious and worrisome. But as Wesleyan University professor Peter Rutland has pointed out, "Chronic ailments, after all, are not necessarily fatal." Even the leading student of the revolution's economic causes, Anders Åslund, notes that from 1985 to 1987, the situation "was not at all dramatic."

From the regime's point of view, the political circumstances were even less troublesome. After 20 years of relentless suppression of political opposition, virtually all the prominent dissidents had been imprisoned, exiled (as Andrei Sakharov had been since 1980), forced to emigrate, or had died in camps and jails.

There did not seem to be any other signs of a pre-revolutionary crisis either, including the other traditionally assigned cause of state failure -- external pressure. On the contrary, the previous decade was correctly judged to amount "to the realization of all major Soviet military and diplomatic desiderata," as American historian and diplomat Stephen Sestanovich has written. Of course, Afghanistan increasingly looked like a long war, but for a 5-million-strong Soviet military force the losses there were negligible. Indeed, though the enormous financial burden of maintaining an empire was to become a major issue in the post-1987 debates, the cost of the Afghan war itself was hardly crushing: Estimated at $4 billion to $5 billion in 1985, it was an insignificant portion of the Soviet GDP.

Nor was America the catalyzing force. The "Reagan Doctrine" of resisting and, if possible, reversing the Soviet Union's advances in the Third World did put considerable pressure on the perimeter of the empire, in places like Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua, and Ethiopia. Yet Soviet difficulties there, too, were far from fatal.

As a precursor to a potentially very costly competition, Reagan's proposed Strategic Defense Initiative indeed was crucial -- but it was far from heralding a military defeat, given that the Kremlin knew very well that effective deployment of space-based defenses was decades away. Similarly, though the 1980 peaceful anti-communist uprising of the Polish workers had been a very disturbing development for Soviet leaders, underscoring the precariousness of their European empire, by 1985 Solidarity looked exhausted. The Soviet Union seemed to have adjusted to undertaking bloody "pacifications" in Eastern Europe every 12 years -- Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, Poland in 1980 -- without much regard for the world's opinion.

This, in other words, was a Soviet Union at the height of its global power and influence, both in its own view and in the view of the rest of the world. "We tend to forget," historian Adam Ulam would note later, "that in 1985, no government of a major state appeared to be as firmly in power, its policies as clearly set in their course, as that of the USSR."

Certainly, there were plenty of structural reasons -- economic, political, social -- why the Soviet Union should have collapsed as it did, yet they fail to explain fully how it happened when it happened. How, that is, between 1985 and 1989, in the absence of sharply worsening economic, political, demographic, and other structural conditions, did the state and its economic system suddenly begin to be seen as shameful, illegitimate, and intolerable by enough men and women to become doomed?

I leave it to the best minds of tHE rHizzonE to provide a response.

oh right rhizzone

ilmdge posted:Thanks dh but that was just a c&p with one or two inserts. It's from FP and it goes on to answer the questions it asks itself but since it's neoliberal I was kind of wondering about the answers 'zoners might have to the same setup/question it posed

miracle on ice, winter olympics, 1980

innsmouthful posted:i hope that wasn't a bit you added

i added the question about what the rhizz thinks and the us's gdp

which anyway is something i find interesting in that article, the USSR's debt/gdp was 1/10th of what america's current ratio is. but the USSR collapsed. the collapse just seems not based on socialist economics at all, then.

ilmdge posted:which anyway is something i find interesting in that article, the USSR's debt/gdp was 1/10th of what america's current ratio is. but the USSR collapsed. the collapse just seems not based on socialist economics at all, then.

i think the classic "neolib" answer to the collapse is because of nationalities issues exacerbated by the loosening of political control by the kremlin. the loosening of political control was necessary in order to enact economic reform, which was gorbachev's overall goal, so the argument goes.

ilmdge posted:How, that is, between 1985 and 1989, in the absence of sharply worsening economic, political, demographic, and other structural conditions, did the state and its economic system suddenly begin to be seen as shameful, illegitimate, and intolerable by enough men and women to become doomed?

the deth of ideology. the green grocer took a shotgun slug to the forehead.

e: i guess this is the neoliberal answer

Edited by cars ()

i guess part of the reason i posted that excerpt was because of fingers's post where he was saying a lot of socialists today try to deny that it failed at all and i wanted to get in on that. as in, obviously the ussr had fatal flaws that led to its collapse, but maybe its socialist economy wasnt one of them? i dunno, who remembers this poll

The problem with those kinds of questions is that they're like asking "was feudalism cool?" or "was George Washington a good president?", you don't get a meaningful answer, as evidenced by the near-total absence of real communist movements in any of those countries.

http://www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/fond-memories-of-communism

So what were those good things about communism? I put this to my wife here in Poland recently. She started enumerating the “good things about communism” that she remembered before the changes. Since the old regime collapsed when she was quite young, the memories must be rather vivid:

Going with your mother to collect bottles in vacant lots to turn in for the deposit so you can buy milk.

Brushing your teeth for one week out of every three months because toothpaste is unavailable or too expensive. (But that’s not too bad since there isn’t any sugar either.)

Having to be extra careful about how much toilet paper you use because it’s hard to get.

Listening to your parents cry in the kitchen because they don’t know how they can buy food for you.

Having your broken leg set (at age ten) by a drunken doctor who doesn’t lay down gauze under the plaster, so that when it has to be taken off and reset, it takes the skin with it. It is taken off with a screwdriver that gouges to the bone.

These were not poor people: her father was a high-ranking officer in the Army Secret Chancellery, her mother a bank manager.

She summed up her feelings toward Westerners who still defend communism and espouse some form of socialism thusly, “These people offend me by existing.”

http://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/photo-gallery-east-germany-s-transformation-fotostrecke-59943.html

Edited by jools ()

most of the people i've met irl who lived under communism as adults seem to think it was a lot better.

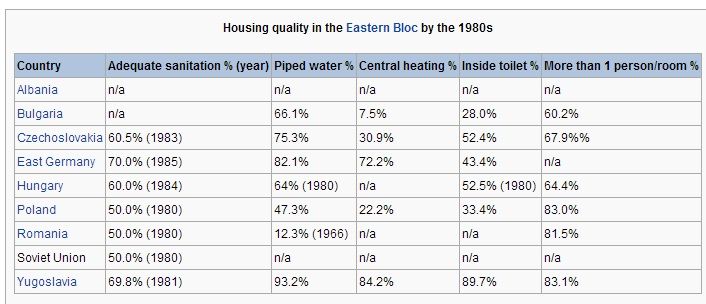

Don't get me wrong. It probably sucked if you worked all your life and savings were destroyed in hyperinflation in 1991. But at least people now have access to things like internet and indoor plumbing.

These were not poor people: her father was a high-ranking officer in the Army Secret Chancellery, her mother a bank manager.

oh look the entitled spawn of two bureaucrats in the revisionist government which dismantled communism turns out to hate communism, what a surprise

what is the source of that data

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Bloc_economies#cite_note-sillince19-138

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_war_crimes

Stalin responded to a Yugoslav partisan leader's complaints about the Red Army's conduct by saying, "Can't he understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometers through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle?"