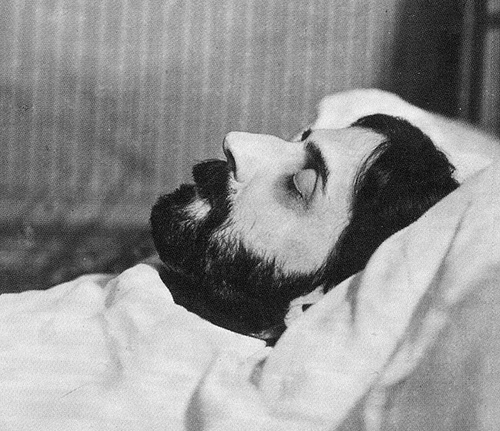

Judging by y'alls' goodreads, most 'Zoners have read Marcel Proust. But whether you've read Proust or not, you've likely heard of "Proust's madeleines," described in the excerpts above. Proust was, among other things, an untrained master of psychology, and in his famous madeleine discourse he describes a sensation everyone has experienced, what he calls "involuntary memory." A taste or a smell recalls to us a pleasant sense of something past, an episode of time in our life (our prior life), sometimes hard to pin down, but which always comes with a sweeping feeling of nostalgia and a giddy sort of happiness. These involuntary memories don't have to be brought on by taste or smell alone, they can also be revived in us by the feeling of two uneven stones beneath our feet, the brush of a napkin on our lips, the clink of a spoon against a glass. In my own experience, these memories are most often attached to music. I'll read a long book while listening to some new album, and that album becomes henceforth the "soundtrack" of a whole period of my life. When, years later, I listen to that album again, I'm transported back to that time, or that book.

There are many different people out there. Most put their heads down and live their lives, not often examining what's around them. Some may be intelligent, but simply not introspective, not artistic, not alert; these people utilize their intelligence writing pages of analysis about the latest episode of Game of Thrones, or, more "productively," arguing the minutiae of some court case.

There are also those people who are more aware. I think many 'Zoners and wddps fall into this category. Some may be depressed, tormenting themselves with insecurities and second guessing, or miserable over their knowledge of the state of the world. Some also, and here I'd probably include myself, see things and feel things, but are incapable of expressing them sufficiently. It's as if, gazing at an enormous orchard of potential expression, we see stretching out to the horizon bright green trees bearing bright red apples, but have at our disposal only those few overripe fruits that have dropped to the ground before us. We simply can't express or even realize the depth of what we know.

"Involuntary memory" is likely a universal type of experience. Others have lived it, and others had even written about it before Proust. But he is the rare artist that sees things and is capable of expressing them. His brilliant language, by seducing the patient reader who plods his way through Proust's works, leaves that reader more receptive to his ideas, more able to relate to them and recognize parts of himself he may otherwise have not.

Proust does not limit himself to discussion of involuntary memory. He observes and has tantalizing insights every few pages, and this continues over the thousands of pages that make up his masterpiece, Remembrance of Things Past. He sees, and when I read him, I think, "Yes! Yes!!"

If I'd read his volumes fully prepared, I would have page after page highlighted in yellow, dozens of little sticky notes protruding from my books. I didn't do that, and even if I had, it would serve me better for a re-read than it would help form the basis of any kind of discussion on da rhizz. What I'll do instead here is focus on one particular part of the human psychology that Proust doubled back on again and again, not only more than any other idea, but which was the driver of entire volumes of the novel.

"I want the one I can't have." This feeling isn't unique to Proust and Morrissey; the phrase "playing hard to get" is part of contemporary vocabulary for a reason. But this emotion seems to resonate particularly with Proust, he comes back to it again and again. If you recall, he was ready to enact a rupture with Albertine until being frightened by her other potential romantic interests into a relationship that ultimately was the backbone of the entire work. Even while living with Albertine, one of the more climactic segments involves Marcel's intense fear of who she may meet out on an expedition one day. He frantically sends Jodi Dean's maid, Francois, out to retrieve her. He receives a reply that Albertine is with Francois on her home, and instantly, his agitation is diminished.

Proust revisits this psychological quirk extensively. In Sodom and Gomorrah, he writes:

Although everyone speaks mendaciously of the pleasure of being loved, which fate constantly withholds, it is undoubtedly a general law... that the person whom we do not love and who loves us seems to us insufferable. To such a person, to a woman of whom we say not that she loves us but that she clings to us, we prefer the society of any other, no matter who, with neither her charm, nor her looks, nor her brains. She will recover these, in our estimation, only when she has ceased to love us.

This is the same theme again beating us over the head, the suggestion is once more that we want what we can't have. But this line of thinking, taken to its natural conclusion, is alarming. According to Proust, one wants what one doesn't have, and, once having it, feels weighted down by it, is unhappy, finds it distasteful. The implications here are astronomic: simply, one can never be satisfied. There is no contentment for us in this life. For, if we are always wanting things we do not have, and rejecting things that we do, there can be no happiness. This, from a master of human psychology.

My initial thought was that maybe this is some defect unique to Proust, or, at least, not common to all men. Simply put, Proust is a genius, and his insight into the human mind is beyond measure. But after all, we're talking here about a mama's boy who never worked a day in his life, who lived with his parents until they were dead; a closeted gay man who, as he went continued with is masterwork, eventually turned every character in this magnum opus (besides himself) into a homosexual (♪♫ if you ever need self-validation / just meet me in the alley by the railroad station /it's all over my face ♪♫).

Certainly, the many people who enjoy lifelong loves and marriages stand as a testament against the implied contention of insurmountable discontent... unless these couples do experience boredom, resentment, or lustful wanderings, and simply do not have the personality to act on these things, simply value commitment above all -- such people, I'd argue, will ultimately lead more happy lives. I myself, from my life's experiences, am entirely confident I could completely commit myself to the right woman for life, and any temptations or unhappiness would be minimal, inessential. And yet I nevertheless connect with Proust's thesis here, except in a different way.

I realized that what's represented above is ultimately one more line drawn under the "I want what I can't have" idea. This excerpt, about a man about to engage in a duel, describes how only then, when he knows his life is at a possible end, does he wish to work, travel, climb mountains, live his life: ie, when he fears he cannot have these things. Is this not the same thesis applied once again, albeit in a different way? This could be the underpinning of the disease called procrastination; one doesn't do things now because one could do things now. We do not want what we have before us. It is only when the possibility seems it is going to be withdrawn that we suddenly regret all we haven't done, just as the procrastinator only begins his project at the last moment before his opportunity will vanish.

Proust himself did not explicitly make this connection, but clearly the description of the man approaching the duel suddenly desiring the utilization of his life is akin to Marcel wanting Albertine after discovering her other proclivities and fearing a loss. Likewise, he no longer wants her when he feels confident in his possession. These are all symptoms of the same disease.

This once again reminds me of myself. I've always been adept at math, scoring perfect on the SAT and ACT when I was young. Perhaps it is for that very reason that I turned away from fields like engineering and autism, at which I could have excelled, and instead am throwing myself into literature and dreams of writing, which I utterly lack the talent for.

What say you, my misshapen virgin creatures?? Will you analyze Proust's art with me??

goodnight 'zzoners

goodnight 'zzoners