I've been reading Capital Volume 1 and it's very good. I finally got through the First Three Chapters a little bit ago which elucidated many things, but the fact is that Marx was writing in the 1800s when money looked very different. I want to understand the economy and Marx will help me, but I can't get ahold of what money actually is today!

Marx's theory as I understand it is that money is a commodity which through historical processes gained a privileged position in exchange as the one commodity set aside as an equivalent for all other commodities to measure their value. Again through historical processes and owing to the special physical properties of gold and silver, these metals became money in virtually all societies. Their value, like all other commodities is dependent on the amount of labor it takes to produce them.

Another function of money is as means of exchange. Now that value is measured in money, the producer of a commodity can part ways with their product and receive an equivalent amount of money in return, essentially transforming the shape (but not the magnitude) of the value they have. Then they can convert the money into another commodity of an equivalent value and consume it for their own needs. Here, money can be replaced with a representative of itself. Whether it's a coin made of copper or a bank note it doesn't matter as long as everyone involved in the exchange understands there's real gold behind it. the representatives of the money commodity can generally only circulate within the boundaries of a country as the state is the obvious authority for creating and regulating bills and coins. To go to another country, coined gold or silver must be melted back down to bullion first.

Being able to exchange a commodity for money rather than for another commodity brings with it the possibility of giving the money later. When the commodity is given away now but the money later, it acts as means of payment.

Ok well that's all great but it SEEMS to break down if gold and silver abdicate their throne. Gold and the US dollar were legally separated in 1971 and there are no longer any currencies in the world which are convertible into gold on demand. This could mean a few things. Maybe money is secretly still representative of gold by economic law. The blog "critique of crisis theory" certainly thinks so. Central banks do have large gold reserves, but compared to the amount of currency the gold would need to back, it's nothing. Maybe money now represents a different commodity, also informally. This doesn't sound right but it's one possibility. Is money, as the bourgeois economics text books say, just based on trust in the issuing government? In that case, how can it act as a measure of value under a labor theory of value?

I will continue my investigations into money and write my findings here as I go, but if you can help me understand money please also post.

The general equivalent point is very important, even if it's less obvious today than back when there were fixed pegs between currency and gold. But then, if appearance and reality were one in the same, as someone once noted, we'd have no need for science. Just as the dynamics of the world economy, power differentials in international trade, etc., are such that we have many reasons to expect that a given commodity's price will deviate from its value, gold never stopped being money, but there are more legal contrivances masking this basic operational characteristic now.

Other things we colloquially think of as money — credit, tokens, derivatives, etc. — are important to consider as well, but we also acknowledge that these each have different origins, functions and behaviors. Early in the money chapter of Zur Kritik, for example, he notes: "During the following analysis it is important to keep in mind that we are only concerned with those forms of money which arise directly from the exchange of commodities, but not with forms of money, such as credit money, which belong to a higher stage of production." Thus, gold is a simplifying assumption, but not of the positivist sort we might associate with Friedman's "f-twist"; it's an assumption rooted in realism, in the most basic economic relations, rather than higher-order politico-legal ones. For this reason I tend to think of gold as rooted in the base, as opposed to the forms of token money that emerge from the superstructure.

Empirically, these token forms (whether paper or bits in an electronic system) are the dominant means of circulation in the world today. And Marx even discusses this very phenomenon (way, way, later, in vol 3), remarking that gold can be completely removed from circulation without inhibiting the process, and yet that gold would (and indeed does) still retain a critical role in international trade, as a sort of world money. Hence the continued importance of gold reserves. For a recent case in point, see Libya:

On April 2, 2011 sources with access to advisors to Salt al-Islam Qaddafi stated in strictest confidence that while the freezing of Libya's foreign bank accounts presents Muammar Qaddafi with serious challenges, his ability to equip and maintain his armed forces and intelligence services remains intact. According to sensitive information available to this these individuals, Qaddafi's government holds 143 tons of gold, and a similar amount in silver. During late March, 2011 these stocks were moved to SABHA (south west in the direction of the Libyan border with Niger and Chad); taken from the vaults of the Libyan Central Bank in Tripoli.

This gold was accumulated prior to the current rebellion and was intended to be used to establish a pan-African currency based on the Libyan golden Dinar. This plan was designed to provide the Francophone African Countries with an alternative to the French franc (CFA).

(Source Comment: According to knowledgeable individuals this quantity of gold and silver is valued at more than $7 billion. French intelligence officers discovered this plan shortly after the current rebellion began, and this was one of the factors that influenced President Nicolas Sarkozy's decision to commit France to the attack on Libya.

A few papers I've found helpful in clarifying the role of gold in Marx's theory of money:

- Claus Germer: "Credit Money and the Functions of Money in Capitalism"

- Germer also had a very strong chapter in the collection Marx’s Theory of Money: Modern Appraisals.

- Alan Freeman's "Geld" is also a good read.

Alan Freeman posted:Marx’s treatment of this question is unique in economics. On the one hand, it reveals him to be far from a simple metallist, in that it contains a developed analysis of symbolic money including an essential distinction between fiat money and credit money (cf Lapavitsas 1991). On the other, he establishes in detailed empirical, as well as theoretical analysis that in capitalist society, an indispensible function of money is to serve as store of value and that credit money is inadequate to this task. The contradiction between the functions of means of exchange, and store of value, erupts in times of crisis when capital seeks ‘real value’. An adequate theory of money must establish what symbolic money symbolises.

Edited by Constantignoble ()

thus much of this, will make black white; foul, fair;

wrong, right; base, noble; old, young; coward, valiant.

...what's this, you gods? why, this

will lug your priests and servants from your sides;

pluck stout men’s pillows from below their heads;

this yellow slave

will knit and break religions; bless the accurs’d;

make the hoar leprosy ador’d; place thieves,

and give them title, knee and approbation,

with senators on the bench; this is it,

that makes the wappen’d widow wed again:

...come damned earth,

though common whore of mankind

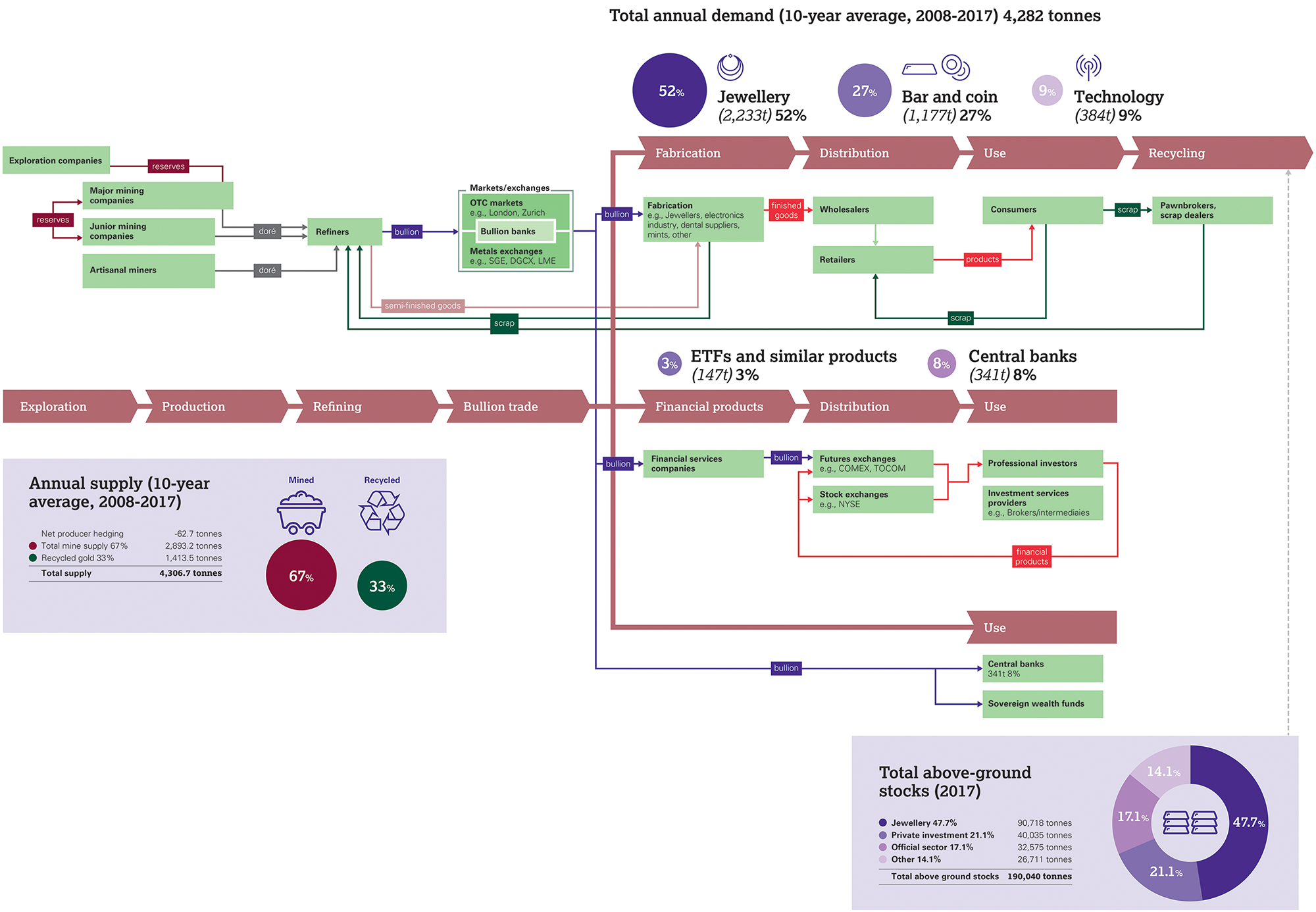

According to a chart on gold.org, more than half of gold bullion produced today goes to create jewelry, 9% goes to the tech sector to manufacture electronics, and only 8% goes to banks. I find it hard to square the fact that more gold goes to create commodities (and not just luxury commodities but technological components which are critical to modern capitalist production) than to financial institutions.

None of these relationships are as clear-cut in the current world economy as they could be, because the nature of the cycle (to say nothing of imperial value transfers / organic compositional differences) is such that price and value decouple increasingly, and credit money, which also grows endogenously, imposes its own value discipline, and so on. The flight to value, then, can mainly be counted on to reassert itself in the depths of crisis, when these higher-order institutional aspects fail.

I've seen some empirical work on gold that attempts to establish it as a de facto standard of price -- such as the conference paper by Matsumoto cited in "Geld," which was able to generate some broad-strokes but iirc not terribly inspiring long-term correlations. I have that one somewhere, but I'll need to dig around a bit, because it's eluding me right now. I do remember he ended it speculating that having better long-term production cost data on gold (i.e., c+v+s) would improve the method.

I think it's an interesting thing to ponder, but getting all the epicycles right is daunting, and maybe not even worth it in the end. Freeman noted elsewhere:

Unfortunately, credit-money is responsible for particular confusion among Marxists, who devote, on average, substantially more labour time to finding fault with Marx’s theory than to understanding it. ... More creditable, but equally mistaken, are attempts to defend Marx by elevating gold to an absolute principle in his theory of money (see Kim 2010, Freeman and Kliman 2011). A more pernicious claim is that Marx ignores or rules out credit, paper money, and all modern capitalism’s financial innovations.

The Kliman/Freeman paper cited in that excerpt is worth a look for its interesting nuance; on one hand, it holds:

Kliman and Freeman posted:All theories of “the age of electronic money” to the contrary, gold still functions as a reserve of banks and central banks. The world’s current monetary system is, in effect, an inverted pyramid based on the exchangeability of all commodities for the dollar, which in turn is based in a complex way on the latter’s exchangeability for gold, or for some basket of gold and other produced commodities. In the event of a full breakdown of the world monetary system, the ultimate commodity basis on which the system rests would re-emerge with great force. In the meantime, it lingers in the background ― in the consciousness of bankers and, in a very complex and mediated way, in the actual rates at which monetary instruments trade in the world’s currency and money markets.

A full understanding of this process requires a further determination, in addition to Marx’s value theory, in order to describe the current, concrete conditions of capitalism. It does not require any modification of the value theory itself.

Yet on the other, it draws on some empirical data to rebut the idea of gold as the sole or even principal causal factor (which is what I believe Freeman was gesturing at by "an absolute principle") in determining the general price level, and further makes a case that the independence of aggregate price, aggregate value, and the value of the money commodity implies that gold itself does not exchange at its value.

So, for this reason, while I appreciate that Sam Williams never let go of the importance of gold, his efforts to direct people to kitco.com to draw straightforward empirical conclusions about the state of the dollar generally ring spurious to me. It calls for a grain of salt, at the least.

(Incidentally, apparently if you take all the gold in use in tech, in jewelry, in money, etc., and melt it all down, it would fill a volume along the lines of three olympic swimming pools. 🌠)

(Edit: oh hey, that's a fun graphic)

Edited by Constantignoble ()